(written August 2012)

In the “Occupy#” movement in the USA from 2011 to 2012, there were quite a few who, when espousing the 99% ideology, claimed that the cops were part of this 99% (revealingly, there were some who also declared that Nazis were part of this 99%). Though the often brutal tactics of the defenders of bourgeois law and bourgeois order tended to rectify most occupiers’ ignorant illusions towards the cops, illusions that the cops are primarily there to “serve and protect” still remained.

On this side of the pond, there are even a few old hands from the traditional workers’ movement who still dare declare that cops are workers in uniform. For instance, the SPGB (Small Party of Good Boys, as they used to be known), stuck as they are in a past before they were born, who point to the 1919 Police Strike, which has gone down in mythology as an example of the proletarian nature of the cops. What these ridiculous people, who try to use the past to justify their present conservative attitudes, show in this is their failure both to understand the past as well as an ignorance about the present which is largely a product of lack of current experience of the cops. “The radical point of view…starts… with a disabused analysis of the present and works backwards. It turns pitilessly on the compatibility of the results of past struggles with the present brutality of human reification, and the inordinate support that insufficient rebellion in the past gives to the glorification of the status quo.” – Chris Shutes, “Two Local Chapters In The Spectacle Of Decomposition”

So what was this insufficient rebellion in the case of the 1919 police strike? Simply put, in 1919 less than 4% of UK cops went on strike.

Previous to 1919 – at the end of August 1918, beginning of September, when Europe was still at war – a 36-hour police strike, whose history is virtually unknown, took place in London (about the only interesting fact that I’ve discovered is that the first thing Lloyd George, the PM, knew about it was when the Met were withdrawn from duty at 10 Downing Street to be replaced by a detachment of the Guards Infantry). In this virtually unrecorded wildcat, possibly 20,000 cops in London went on strike for a wage increase – this at a time when the average copper was getting less than an unskilled labourer and only a third of the take-home pay of a munitions worker. This strike was unlawful and “labelled mutiny by the Home Office” (A.V.Sellwood, Police Strike – 1919). With the mutiny at Verdun a recent terrifying memory for the ruling class, along with the revolutionary upheaval in Russia, plus other revolutionary rumblings, the Lloyd George government quickly gave the cops a pay rise and hinted that they might allow them to have a union after the war, which of course, was denied them later on. From then on, until the more famous failed strike a year later, both sides in this battle tried to prepare for what they knew was coming, though the state exploited best the contradictions of the cops wanting the rest of the working class to support them in the struggle for union recognition. At the beginning of June 1919 there was to be a rally of all the big unions alongside of the nascent illegal police union struggling for recognition. But just 6 days before, on 27th May, there was a bloody clash between members of the Discharged Soldiers and Sailors and the Met, when the latter tried to stop the former marching on Parliament. In a battle that raged along the entire length of Victoria Street, the demonstrators used scaffolding poles and paving stones to inflict more than 150 casualties on the cops, over 20 of them serious. The cops, of course, did their usual beating and batoning, as usual (so far) giving worse than they got. The leader of the would-be union, the NUPPO (National Union of Police and Prison Officers), J.L.Hayes, issued a press statement on behalf of the NUPPO apologising for the cops’ behaviour, putting the responsibility purely onto the government: ‘We appeal to the discharged soldiers and sailors not to judge the union on yesterday’s happenings. Let them blame the Government, the Home Secretary, the Commissioner of Police, and the military system against which we are strenuously fighting. As a union we look upon our comrades in the workshops and from the army as comrades.’ Here we see the socialist ideology of a movement which still had illusions in a hierarchical specialism in the maintenance of a Law’n’Order that could somehow be on the side of the proletariat, whilst at the same time playing their assigned role of defending the bourgeoisie’s precious Parliament. Today, one can hardly imagine the Police Federation participating in a TUC conference using such rhetoric as Hayes to attack the government, even if the TUC is known as the Tories’ Unofficial Cops, and even if the Police Federation is pressurising the government for more cop funding. At that time, both seemed to be very openly antagonistic to the government, using a “solidarity with our comrades”-type vocabulary. Yet, although at the beginning of June 1919, the vote for striking was over 90% in favour (44,539 for, 4,324 against) when it came to actually striking in August, the government having given wage, and social wage, increases to the cops, only just over 3% went on strike. The sole reason for the strike was union recognition, and the state was never going to give that because of their fear that the armed forces would also demand a union. As the Daily Mirror said, shortly after the 1918 strike: “The Prime Minister is to be congratulated over his wise decision not to grant official recognition to a police union…It should never be forgotten that the police are a semi-military body. They are an army defending law and order…An officially recognised trade union of policemen might well lead to an officially recognised trade union of soldiers and sailors.” The British ruling class were well aware of how the Soldiers and Sailors committees and councils had played a significant part in the Russian revolution, which they were still in the process of trying to destroy through their support for the White armies, etc.

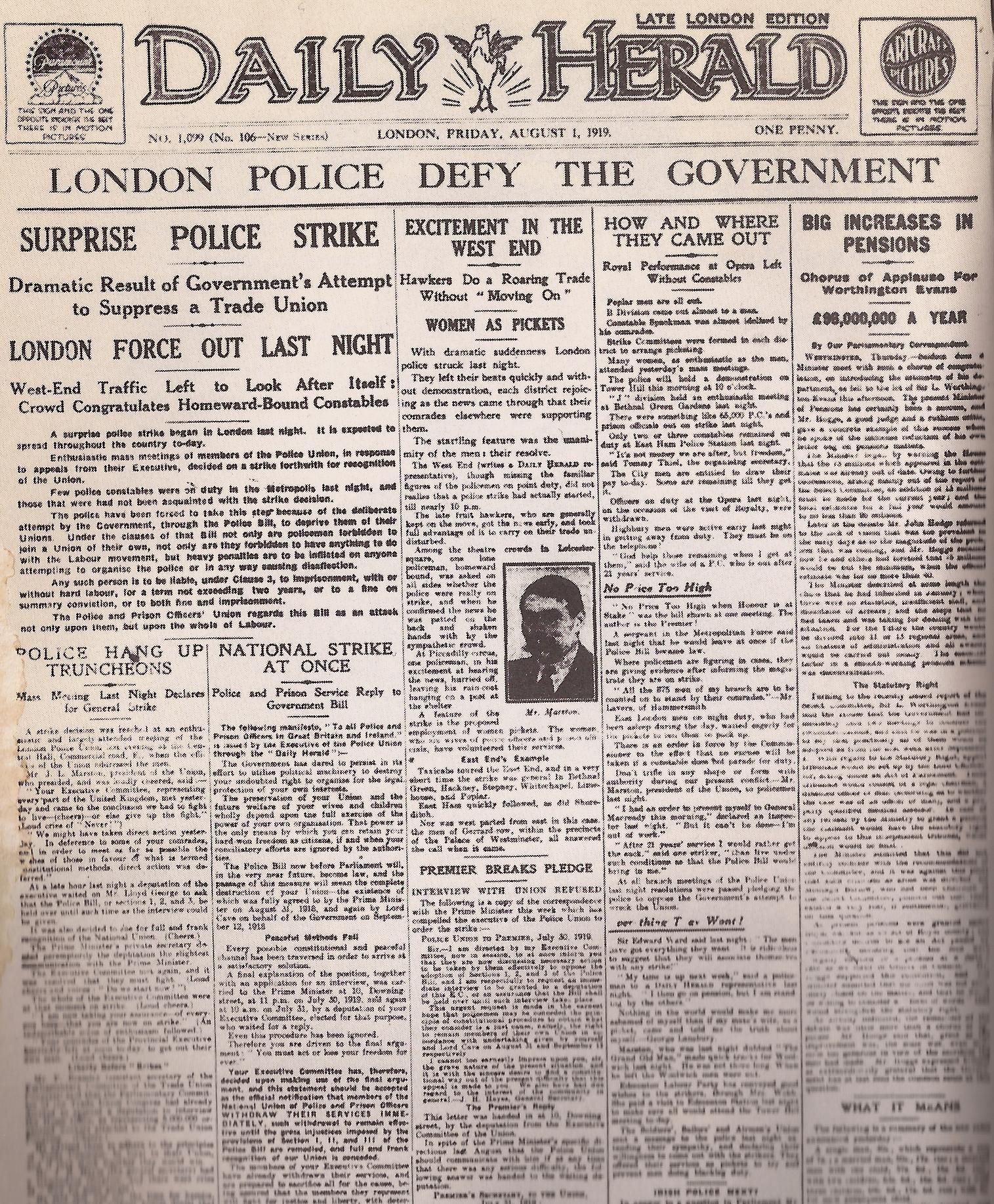

The Daily Herald, under the editorship of George Lansbury, consistently and enormously exaggerated the extent to which the strike was being adhered to by the cops.

The Daily Herald, under the editorship of George Lansbury, consistently and enormously exaggerated the extent to which the strike was being adhered to by the cops.

The 1919 strike itself is only interesting insofar as it shows how little solidarity with the defenders of the state refusing to act their assigned role can be expected amongst these people who have so definitely chosen such a fundamental hierarchical function. As I said, over 96% of the cops never went on strike. And it was mainly in Liverpool that the strike was followed. In London only 965 of the Met went on strike, and of the City Police Force, only 58 came out. And elsewhere, virtually none. The mentality that goes with being a cop is hardly one conducive to expressing practical solidarity with those who were almost certainly going to get the sack as a result of striking, to risk getting sacked for such reasons or to identify with actions that launch a breakdown of bourgeois law and order.

What is more interesting than the internal development of the strike, is the riots that happened as a result of such an opportunity presenting itself, particularly in Liverpool. Although in London there was a bit of looting (e.g. a jewellers in the Old Kent Road got stripped of almost everything and a nearby greengrocer’s, a tobacconist, a draper’s and two smaller shops were looted, along with a clothes manufacturer, where half the stock was taken – rolls of cloth, scores of raincoats, etc., the stuff being taken away by stolen car), the best bits of proletarian shopping happened on Merseyside.

When the cops went on strike at the beginning of August, the first mass attempt at looting in Liverpool was the first Friday night of the strike when a crowd of men, women and kids smashed their way into Sandon Dock, battering down the gates. There were just 11 cops hidden inside, but armed with staves and given the order to beat the shit out of the “mob”. Most of these had been hastily recruited demobbed soldiers who’d been brutalised by the trenches of the war and far from having qualms about cracking skulls and breaking limbs, were enthusiastically into it. In the minds of ruling class ideology, the justification for the use of the brute force of the cops, this “mob” were “Dock rats reeling like ships in a storm from the drunken spite within them, and brandishing a weaponry of axes, sticks and crowbars…a pack of wild women, hair streaming over shawled shoulders, ready to back them with their talons, grasping bricks and broken bottles…rodents, bloody rodents every one of them” (Sellwood, ibid, P.126). The same language deriving from social apartheid as the reduction of the rioters of August 2011 to “feral youth”. So much easier to impose vicious class “justice” on crowds if one thinks of them as savage animals, an ideology that helped develop the British Empire. Sadly, the filth succeeded in defending the contents of the dockyards from these uncivilised scum and their subversion of the ‘civilised’ logic of exchange value.

The Mayor of Liverpool had enlisted 700 troops from the local garrison to guard the key points of the town – docks, railways, power plant, post offices and banks, but he was wary of exacerbating things by giving them any right to fire, and with the cops that remained loyal to the state (under half of the total), he was clear that the rules of property in the city as a whole couldn’t be upheld.

On Saturday night, when the cops turned up at a large department store – Sturla’s in Great Homer Street – they found the store totally stripped of everything that couldn’t be nailed down, and the rest – light fittings, show cases and dummies – had been trashed; even the window frames and the store’s carpeting had been nicked. The cops had expected a battle between the different religious factions of the Irish, of which Great Homer Street was the dividing line – but it appeared that proletarian unity had won over. In nearby Birkenhead, a pawnshop was stripped of its contents, and passers-by were encouraged to join in to share the good fortune of the looters. 3 more local shops were looted that night. Most of the Birkenhead looters received 2 to 3 months in prison (compare that with the almost 18th century-style draconian sentences handed out to the August 2011 rioters). In Scotland Road in Liverpool itself, a jewellers was broken into by a gang and then everyone else was invited to join in: the shop was empty within minutes, followed by the tobacconist’s, the tailor’s and a furniture store. “The women went for the clothes shops, the men for the pubs and whisky stores. The children went for the sweetshops.”, said an eyewitness. A distillery was broken into and the booze shared out. “Some men with iron bars were smashing shop windows and doors without even bothering to enter the premises, content to wage destruction for destruction’s sake” (Sellwood, ibid, p.146). The scab cops batoned left, right and centre. “Hooligans…looking for a fight…ripped cobblestones from the alleys to bombard the police as they re-formed. On three occasions [a particular cop]’s helmet was knocked off, such was the force behind this hail of missiles – and each time he manoeuvred dazedly through the crush to pick it up again. He felt protected, almost naked, without his headgear: besides, he did not want the enemy to sport it as a trophy”. (Sellwood, p. 147).

“Farce and drama, good nature and brutality, both went hand in hand in the London Road as the rioting increased, embracing not only the small-time villains but all sorts of unlikely converts to their cause from the ‘respectable’ and well-breeched. At one point the rioters had grown so bold that they switched on the electric lights of the shops they pillaged, while a group who had broken into one of the district’s departmental stores started generously distributing the loot. Ladies’ mantles, blouses, stockings, dresses of all sorts were passed through the shattered glass of the window to a crowd of women ‘shoppers’, cheering as each ‘gift’ arrived and blowing kisses. It was an almost festive occasion…” (Sellwood, ibid, pp149-59)

looted store, liverpool 1919

The following reveals a detail about both rioters’ and cop tactics during that time: “A favourite tactic with the rioters when confronted by opposition in force was to fall back, split up and take to the side streets. There they would wait until the advance moved on, when the would re-emerge and return to looting. Now, however, it was planned that a mixed force of the CID and specials would follow behind the main advance, but at a considerable interval, so as to swoop on the enemy when he thought himself at his safest, catching him in a trap.” (Sellwood, pp 170-171).

“We now protect our banks with tanks” scrawled on this photo of a

“We now protect our banks with tanks” scrawled on this photo of a

tank guarding Liverpool’s main bank

Rushed south from Scapa with the battleship Valiant, the appropriately-named destroyer HMS Venomous guards Pierhead.

The navy sent a battleship up the Mersey and tanks were sent by the army to guard various important buildings. “Though destined…never to move an inch against the rioters, the tanks fulfilled a vital role in publicising – and much exaggerating – the extent of the army’s presence and commitment….The tanks would be good propaganda value; and this at a time when the facts were dismally discouraging to ‘authority’.” (Sellwood, ibid, P.148). Nevertheless, troops were sent in to attack the rioters, fire over their heads and at one point, bayonets were fixed to the ends of their rifles so they could stick them into the rioter’s butts, though they’d been ordered to only stick them in a bit, to injure not to kill. “Accompanying the troops was an armoured car but as the vehicle came to a halt it became clear that the machine gun projecting menacingly from its turret was to serve, on this occasion, a purely ornamental purpose. For suddenly, the turret lid swung open and out climbed the well-known figure of a certain city magistrate notoriously unloved. For a moment the crowd, curious as to the reason for this most unexpected visitation, paused in its clamour to let the man speak. But no sooner had he begun to read from the scroll he unfolded before him than their temper changed to fury. He was reading the Riot Act. Nervously the magistrate rushed through his lines and then, with a volley of bricks and stones around his ears, he jumped gratefully back into his armoured refuge…As the troops moved slowly forward the crowds began to fall back…And as they did so, the toll of the night’s disorders, no longer concealed by the milling crowds, was revealed in all its magnitude…The entire length of the London Road was fringed with shattered glass, much of it turned into a glittering frost beneath the street lamps by the boots of police and rioters, pounding it into powder. Doors littered the paving stones, or else hung from torn hinges between gaping holes that once were windows, stripped of blinds and shutters by the cupidity of the crowd. The whisky distillery had been gutted, even its ‘empties’ having been used as ammunition against the police. The nearby chewing gum factory had been stripped completely bare by a crowd that, so rumour went, had consisted largely of children…Yet curiously, the aspects of the forbidding scene that were to live longest in the memories of the recruits were trivial…The man on crutches whom they saw hobbling down the London Road, with a pair of boots in each hand and several more suspended from his neck…The old lady who, appearing to be inordinately fat, was found to be wearing eight corsets over her dress, concealing them…And then there was the ‘generous’ looter who, having swag to spare, had kindly offered some of it to a needy-looking character – a CID man, who booked him on the spot….Vast quantities of supplies newly landed from America were looted from the sheds of the Wellington Dock, and wholesale pillaging broke out in the others..Some of the women had brought em;pty prams and pushcarts to the scene to carry home their share of the pillage. For there was plenty for all and the mood of the rioters was generous. At one point, a group of children were seen sitting on the kerb outside a shoe shop, breaking open cases of shoes and trying to match them with their feet. All that did not fit they hurled into the roadway. Further on, having ransacked a furniture store, the mob had stacked together all the items that were too heavy to carry, and made a bonfire of the pile, dancing around it as it blazed…[Certain cops were] greeted by the sound of music: the latest ragtime hits being punched out on a piano…They rounded the corner…to be confronted by the spectacle of a grand piano along the kerbside with a host of drunken figures, men and women, beating out the time with mugs, bottles and fists, and egging the pianist on. The piano, sole survivor of many such in Crane’s music shop, had been dragged out of the window by the mob.” (Sellwood,ibid pp 151 – 155, 181). In the London Road, in a stretch less than 600 yards long, over 200 premises had been broken into and most of them stripped bare. A factory and distillery had been gutted and masses of plate glass destroyed. A scab cop later said, “Altogether it looked as if a good time was being had by all. And a pity perhaps to spoil it: but we did – and willingly.” (Sellwood, ibid, p.181)

Eventually, a rioter – Cuthbert Thomas Howlett – was shot and killed by a soldier, Lance Corporal Seymour, who pleaded justifiable homicide and was found not guilty. It had been in an attack on warehouses and bottling stores crammed full of booze. “Bottles by the crate-load had been sacrificed to the immediate thirst of the crowd. Hundreds more had been loaded for transit to ‘safe places’…they had smashed every bottle they could not empty or send away in the carts and barrows…Cask after cask was broken into and emptied…” (Sellwood, pp161-162). When prisoners were taken by the combined forces of the army and scab cops, Howlett was killed in a mass attempt to free them from the prison vans. Like David Moore, the cripple killed by cops in Liverpool running him over on the pavement the night before the royal wedding of Charles and Diana in 1981, this state murder is largely unknown.

According to Sellwood, “The Union leaders…issued a strong denunciation of the riots and condemned the violence from which, as it pointed out, the Labour movement had everything to lose”. (ibid, p.186). Quite right: the representatives of the struggles of the working class inevitably have everything to lose from the autonomy of the class. Those who still seem to think that unions and the labour movement have something to offer the working class are only right insofar as workers still want to remain workers and identify with their role in the miserable status quo, identify with their chains.

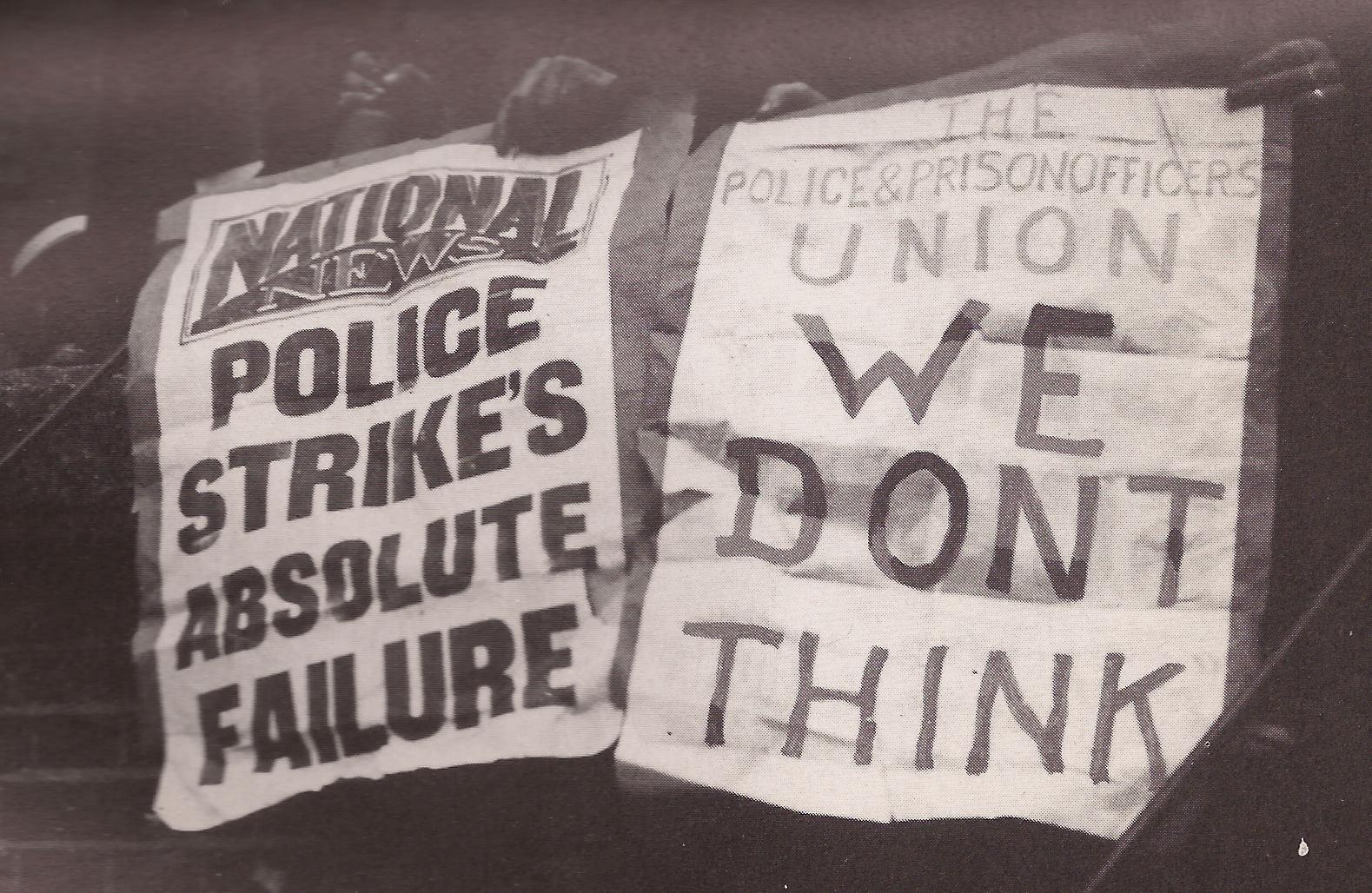

The strike itself was a failure, since the only motive for it was to get union recognition. Cops, having been promised a state body which would provide them with the means to register their complaints (the precursor of today’s Police Federation), and having been given all the financial demands they’d struck for in 1918, had little reason to support a strike that in fact undermined the class basis for their whole existence. 2300 strikers were consequently sacked (of whom 955 were in Liverpool) and the Liberal government instituted a very clear anti-strike clause in the police’s contracts. No sector of the working class had come out in support of them, despite having said they would. A factor in this lack of support, at least for Liverpool, was that Liverpool workers still remembered the “Bloody Sunday” of 8 years previously when in 1911 a Protestant carter and a Catholic docker were shot dead, the funeral becoming an occasion for sectarianism to be swept aside in a massive display of working-class solidarity.

Since then, the police strike has been so passed into the land of misty myths that, at the London march against the more modern Bloody Sunday, the Derry massacre in 1972, I found myself next to a fellow student who screamed at the cops “Remember the 1919 strike!”, as the cops ran out between the towering horses truncheoning people left, right and centre. Clearly the guy himself had no memory of it other than what his Trotskyist party had taught him to believe. Having gone from Catholicism to Trotskyism in a matter of weeks, he obviously believed in the power of conversion. But this was Whitehall, not the Road to Damascus.

See also this extract from Ken Weller’s “Don’t be a soldier!”

2255

Leave a Reply